How A Public-Private Partnership in Illinois Gives More Seniors Access to Assisted Living

A Conversation with Executives of Gardant Management Solutions

The 50 U.S. states are often called the laboratories of democracy. They create innovative programs that can be tested on a local level before being rolled out to other states, or the entire nation.

The 50 U.S. states are often called the laboratories of democracy. They create innovative programs that can be tested on a local level before being rolled out to other states, or the entire nation.

About 20 years ago, Illinois launched the Supportive Living Program. It provides assisted living services in dedicated, licensed communities to low- and moderate-income seniors under a Medicaid waiver provision. Residents use social security to pay the cost of room and board, though they are allowed to keep $90 a month for personal expenses.

The idea is especially relevant today as the number of middle-income elders is expected to grow to 43% of the population over age 75 by 2029, according to NIC’s groundbreaking study, “The Forgotten Middle.”

NIC chief economist Beth Mace recently talked with top executives of Gardant Management Solutions. The Bourbonnais, Illinois-based company is the largest operator of supportive living projects in the state.

Here is a recap of the conversation with Rod Burkett, CEO of Gardant, and Greg Echols, CFO of Gardant. Rod, who also serves on the board of the Affordable Assisted Living Coalition, explains how the program works and why it matters.

Mace: How did Gardant get started?

Burkett: Gardant was founded in 1999 by me, and a former partner, in response to the creation of the Illinois Supportive Living Program which was started in 1997. It was designed as an efficient alternative to nursing home care. The state has licensed 155 supportive living facilities which provide assisted living services to low- and moderate-income seniors through a Medicaid waiver.

Mace: What is Gardant’s mission?

Burkett: Our goal is to increase accessibility and affordability in the assisted living sector. We felt the Supportive Living Program was a good way to help make that happen. We have a strong desire to enrich the lives of seniors and their families, and to focus on providing a high standard of service and care. We place a high value on people—those we serve, employees and business partners.

Mace: How many projects do you operate?

Burkett: Gardant has grown to become a large regional operator with 62 projects, mostly assisted living communities. We are one of the largest operators of Illinois’ Supportive Living Program. We also have a growing footprint in Indiana. Gardant has a minority ownership position in about 60% of the properties we manage. The other 40% are operated under third-party management agreements.

Mace: Greg, tell us about your role.

Echols: I joined Gardant as CFO about two years ago. My background includes public practice as a CPA prior to a transition to private industry and commercial real estate, and then senior living. I joined a large owner/operator and remember visiting a community and meeting a resident who came over to shake my hand. He wanted to thank me for being part of the organization and said he had made the last best decision of his life by moving to the community. That statement made such an impact on me. I felt my career purpose had become aligned with the industry.

Mace: What is the Affordable Assisted Living Coalition (AALC)?

Echols: Gardant is one of three founding members of the AALC which was launched in 2003 under the leadership of Wayne Smallwood. He spent 30 years at the Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services, which runs the Medicaid program. The AALC strengthens and promotes the Supportive Living Program, and provides participating members with training and education, along with political advocacy and lobbying efforts. The AALC also offers a scope of member services including financial source awareness for our sector.

As far as we are aware, the AALC is the only trade association in the nation that focuses on an affordable, Medicaid-waiver model of assisted living with all its unique regulations and challenges.

Mace: How many residents participate in the Supportive Living Program?

Burkett: The current capacity of the program is about 12,500 residents in 155 supportive living facilities. About a dozen of the properties provide services for the physically disabled age 22-64. No new supportive living licenses are being issued. But a few locations for the elderly are piloting dementia care programs.

Mace: Is there unmet demand?

Burkett: Our supportive living portfolio runs at about 94-95% occupancy. There are supportive living facilities in 75 counties in Illinois. Larger secondary markets have several facilities and most Chicago neighborhoods have one. Private pay assisted living has filled in the market over time, so the state decided not to keep awarding supportive living licenses. The AALC agrees with that policy so the market does not become oversaturated since supportive living operators are already taking lower, and slower, reimbursements from Medicaid.

Mace: Are all the supportive living properties and operators members of AALC?

Burkett: About 95 percent of the 155 facilities are members. There are no skilled nursing or independent living communities in the Supportive Living Program. But some nursing home operators with nearby supportive living facilities are members.

Mace: Do other states have similar programs?

Burkett: I’m not aware of any other states that tie the building to the program. It was a progressive move by Illinois to take this approach. Other states haven’t made this commitment to the affordable model. It results in a cost savings by keeping people out of nursing homes. A supportive living facility must reserve at least 25% of its apartments for Medicaid recipients. A supportive living facility can charge private pay residents a higher rate.

Mace: What percentage of residents in your buildings are private pay?

Echols: One-third to 40% of the resident base is private pay.

Mace: How do you measure success? Occupancy? Length of stay? When you conduct a self-assessment, what do you look at?

Burkett: We measure all the factors you mentioned. But one of the most important measures took place at one of our first buildings in Decatur, Illinois. It opened July 1, and 31 people moved in that day. Of those, 26 came from nearby nursing homes. They did not need to be institutionalized. There was no other Medicaid service level available to them unless they were in their own homes. The supportive living facility was the missing piece of the puzzle. The state saved 40% on its Medicaid budget for each one of them for that day and every day thereafter that they would have otherwise been in a nursing home. That’s the biggest success. The dollar savings and the impact on those 26 people who have their own apartments.

Mace: Is that 40% ratio of savings still relevant?

Burkett: When the first building opened, the supportive living rate was 60% of the nursing home rate. Now it’s 54.3%—a bigger savings now. Supportive living facilities play a role in keeping people out of nursing homes, or at least delaying it by a year or two.

Mace: Has the program impacted the seniors housing industry more broadly by offering a more competitive model than exists in other states?

Echols: We supplement the dynamics of the industry by providing an option for seniors who might otherwise be institutionalized.

Mace: Are the rooms in supportive living facilities different from those in private pay buildings?

Echols: When I joined two years ago, I toured the communities. They feel no different than competitive private pay buildings. They look the same and function the same, and residents talk about their experience in the same way.

Mace: How is government oversight handled?

Echols: Illinois created a separate licensure program for supportive living under the Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services. But the regulations are like those for assisted living which is licensed by the Illinois Department of Public Health. We have annual inspections and other requirements. You would have to look at the license on the wall to tell if the property was assisted living or supportive living.

Mace: NIC recently spearheaded research on the growing group of middle-income seniors that will need housing. Does this group fit within the mission of AALC, or is the focus on low-income seniors?

Burkett: The AALC is focused on both groups.

Mace: Is the capital stack different for supportive living facilities?

Echols: The capital stack of debt and equity compared to other seniors housing development deals looks the same. But equity sources underwrite the product differently. They have a legacy hold strategy and are looking to add appreciation value of the real estate over time. As a result, underwriting for these projects may not have the same characteristics as a five- or 10-year IRR analysis.

Mace: Is it an advantage that a limited number of properties participate in the program?

Echols: That is the case in Illinois. We are not aware of new licenses outside of the memory care pilot program and a few supportive living facilities that have been licensed but not built yet.

Mace: Who are your debt providers?

Echols: The debt sources are the same from a construction and new development standpoint. We look to HUD financing for new construction. Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) also work well with this product. Gardant has operated some LIHTC communities long enough that we are approaching the end of the tax credit period. Those projects have appreciated and will transition to a long-term financing strategy with HUD. The projects must still provide services for low-income residents for 15 years. After that, the asset has no use restrictions. Again, the investment horizon is that of a long-term hold.

Mace: Who are the equity investors?

Echols: High-net-worth individuals.

Mace: What are the investment returns?

Echols: In a hypothetical liquidation scenario, and in particular for LIHTC deals being recapitalized and providing an exit for the tax credit syndication, the IRR’s are very comparable to a traditional deal structure.

Burkett: To reach those comparables, there must be a minimum of 100-130 units. That’s the sweet spot to cover the cost of dealing with the bureaucracy of Medicaid and tax credits. It would be hard to do 50 units with the extra legal and billing costs. LIHTC is a good equity overlay for Medicaid reimbursement. But we have used conventional equity as well. We don’t know what Medicaid will pay years from now. But there have been enough investors that are comfortable with the model that it has had good growth.

Mace: Has there been any struggle to get reimbursements considering the budget challenges faced by Illinois?

Burkett: When Greg joined us, it was one of the worst times. Payments were running about nine months behind. Now it’s running in the 90-120-day range.

Echols: Another underwriting aspect of these deals is the need for a reserve position to buffer the timing delay of remittances between billing and payment. It requires a cash reserve or line of credit which can compensate for 4-6 months of delay in billing vs. payment.

Mace: Any other thoughts? Lessons learned?

Echols: This program represents an opportunity for other states. There’s tremendous value in learning about the Illinois program and its combination of successful resident outcomes, and lower Medicaid spending.

Burkett: Each state has its own way of doing things and there are varying degrees of buy in for this model vs. institutional care. But it’s something to think about.

Uncovering Relationships Between Occupancy and Rent Growth in Assisted Living Property Markets

By Lana Peck, Senior Principal, NIC

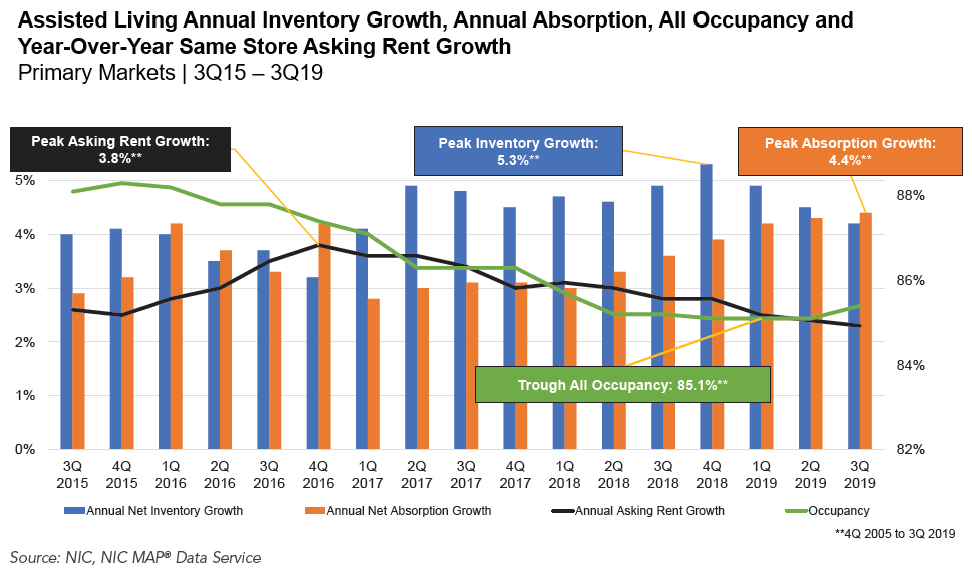

In evaluating the attractiveness of a market for seniors housing investment or development, supply and demand metrics are crucial data to examine, and layering on an assessment of rent growth and occupancy may provide additional insight. The following analysis shows the relationships between average occupancy rates and rent growth patterns for assisted living for the past four years—from 3Q 2015 through the current quarter of 3Q 2019—for the NIC MAP® 31 Primary Markets in aggregate—and then looks at the relative performance of individual markets.

In evaluating the attractiveness of a market for seniors housing investment or development, supply and demand metrics are crucial data to examine, and layering on an assessment of rent growth and occupancy may provide additional insight. The following analysis shows the relationships between average occupancy rates and rent growth patterns for assisted living for the past four years—from 3Q 2015 through the current quarter of 3Q 2019—for the NIC MAP® 31 Primary Markets in aggregate—and then looks at the relative performance of individual markets.

The four-year timeframe provides a recent look-back at the time series’ peak assisted living rent growth, inventory growth and absorption, and the time series’ low occupancy rate. The abbreviated time frame seeks to mitigate any potential confounding effects of the Great Recession on the market fundamentals. As the data is considered, it is important to note that the results would differ if the study took a one-year, two-year, or ten-year look-back, with greater or lesser fluctuations in market dynamics on display with various timeframes.

The impact of supply and demand on occupancy and rent growth patterns

Assisted living same store annual asking rent growth for the 31 Primary Markets has softened since the fourth quarter of 2016 when it peaked at 3.8% (as shown by the four-year time series snapshot in the chart, below). One factor in the decline has been the recent acceleration in net annual inventory growth rates (a measure of supply) which exceeded annual rates of net absorption (the change in occupied stock—a measure of demand) in the quarters 1Q 2017 to 2Q 2019. During this timeframe, total net inventory exceeded total net absorption by nearly 11,000 units (31,212 versus 20,317 units, respectively).

On the supply side, annual net inventory growth peaked at 5.3% in 4Q 2018. Since then, assisted living inventory growth has decelerated to 4.2% in 3Q 2019. In contrast, on the demand side, annual absorption growth peaked in 3Q 2019 at 4.4%–the highest level reached since NIC began reporting the data in 4Q 2005.

The assisted living all occupancy rate in the 31 Primary Markets (which includes properties still in lease-up) declined over the past four years, continuing the downward trajectory that began in 3Q 2014. This has put downward pressure on rent growth rates. In fact, the first and second quarters of 2019, and the fourth quarter of 2018, registered the lowest occupancy rates since NIC began collecting the data in late 2005 (85.1%). While the all occupancy rate in the third quarter of 2019 increased by 30 basis points to 85.4%, annual growth in the average annual same store asking rents for assisted living has been decelerating, and this pattern continued in the third quarter when annual rent growth slipped back to 2.3% from 3.8% in late 2016 and 2.8% one year earlier. By and large, lower occupancy equals lower pricing power and reflects the challenging leasing environment that many operators are experiencing today.

Market-level occupancy and rent growth performance

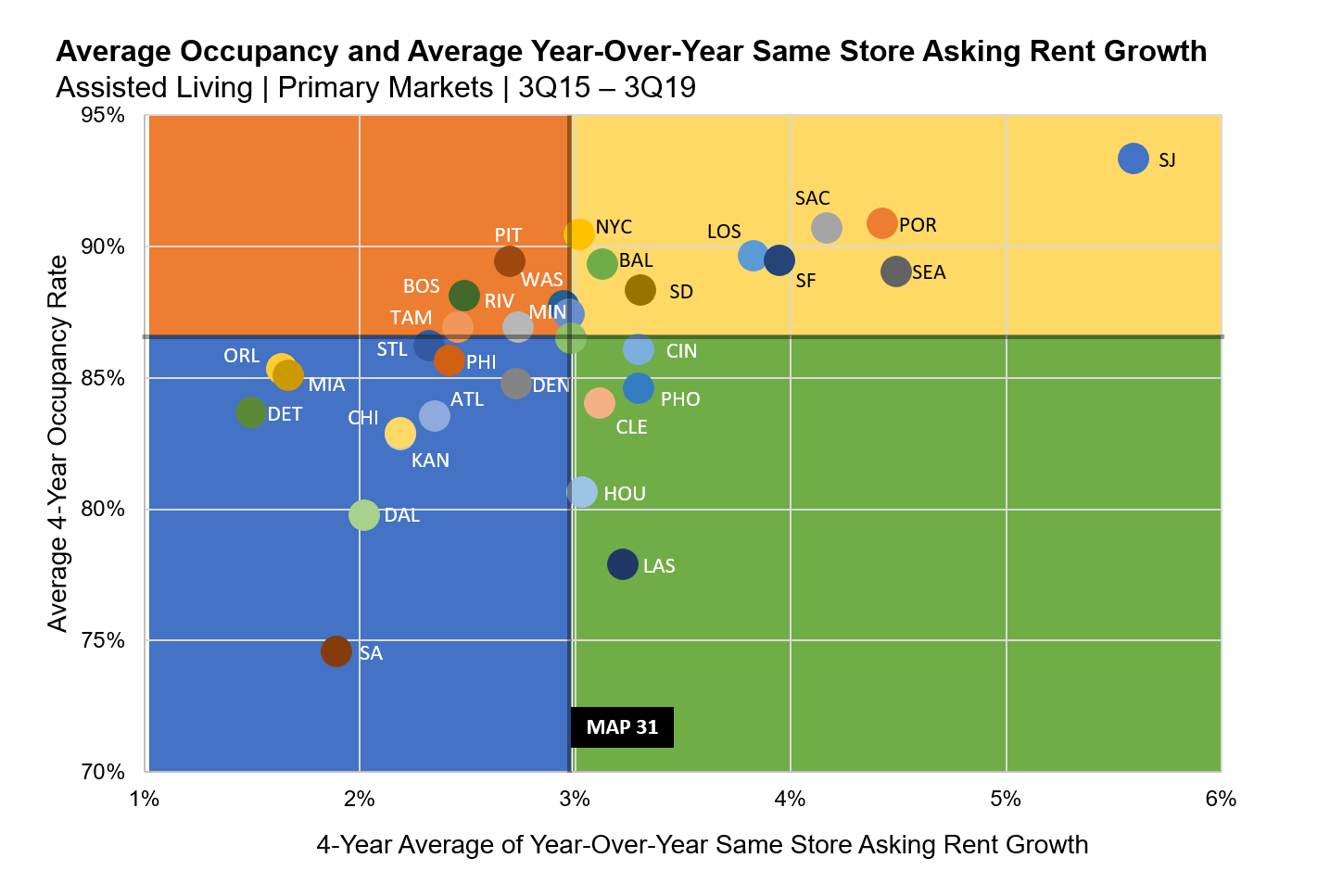

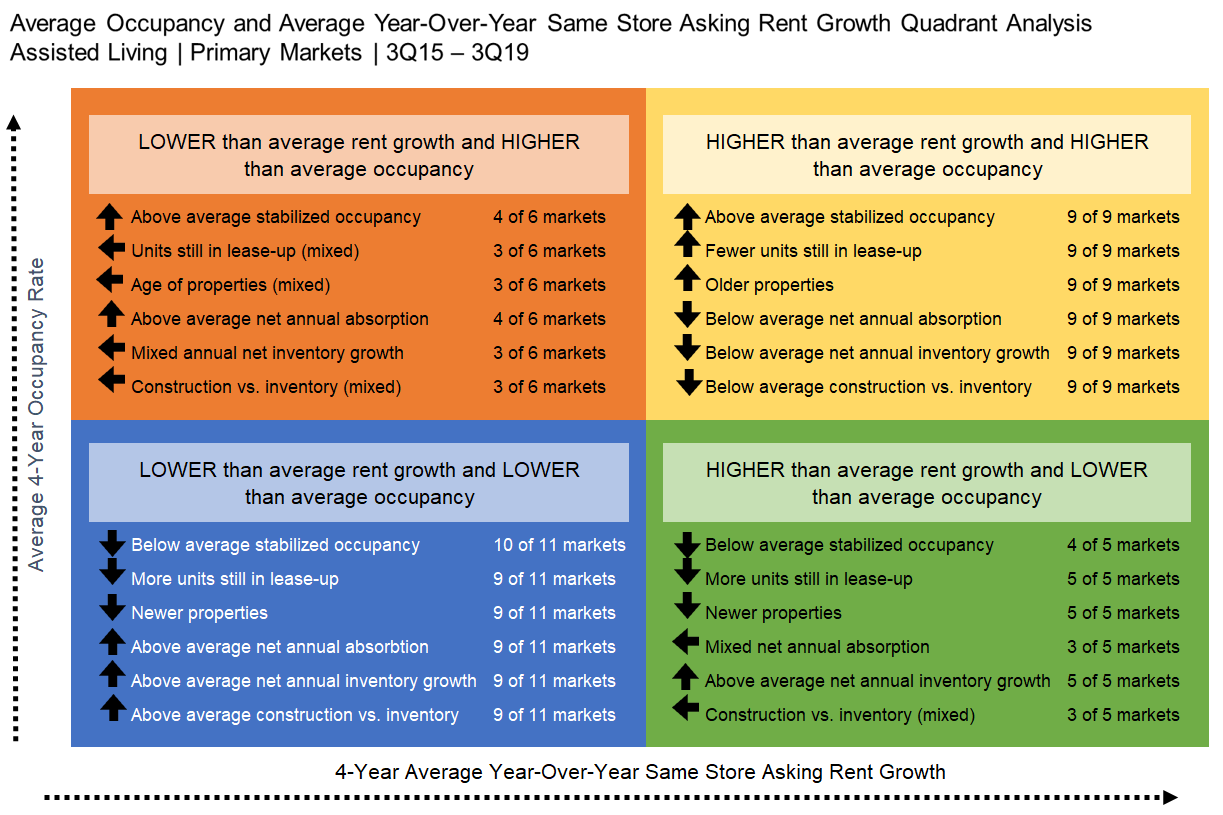

As shown in the following chart, data for each of the 31 NIC MAP Primary Markets was plotted for the last four years (3Q 2015 to 3Q 2019) to understand the relative performance of rent growth and occupancy trends. The chart displays each market’s performance relative to each other and to the Primary Markets’ average for annual same store asking rent growth and average occupancy for this four-year period (for the Primary Markets, rent growth averaged 3.0% over this period, while the occupancy rate averaged 86.5%). The differing colors for the markets help distinguish each market’s plotting relative to that of the others.

- Nine markets in the upper right quadrant had higher than average annual rent growth (ranging from 5.6% in San Jose to 3.0% in New York City) and higher than average occupancy (ranging from 93.3% in San Jose to 88.3% in San Diego).

- Eleven markets in the lower left quadrant had lower than average rent growth (ranging from 1.5% in Detroit to 2.7% in Denver) and lower than average occupancy (74.6% in San Antonio to 86.2% in St. Louis).

- Six markets in the upper left quadrant had lower than average rent growth (ranging from 2.5% in Tampa to 3.0% in Minneapolis) and higher than average occupancy (89.4% in Pittsburgh to 86.9% in Tampa and Riverside).

- Five markets in the lower right quadrant had higher than average rent growth (ranging from 3.3% in Phoenix and Cincinnati to 3.0% in Houston) and lower than average occupancy (ranging from 86.1% in Cincinnati to 77.9% in Las Vegas).

*Source: NIC, NIC MAP® Data Service

The strongest performing markets—those with the highest assisted living average annual asking rent growth rates and highest average all occupancy rates for the past four-years included San Jose, Portland, Sacramento, New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Baltimore, Seattle and San Diego. Many of these markets have limited supply due to constraints such as significant land development regulations, physical constraints on geographical expansion, and extended entitlement processes and/or premium prices on land due to scarcity. Building seniors housing may also not be considered the highest and best use of land, with other types of real estate taking priority. Investors and developers in markets with these characteristics tend to have a long-term hold strategy and are typically rewarded with the ability to maintain or command higher rents because of relatively more restricted competition.

The weakest performing markets—those with the lowest assisted living average annual asking rent growth rates and lowest average all occupancy rates for the past four-years included Detroit, Orlando, Miami, San Antonio, Dallas, Chicago, Kansas City, St. Louis, Atlanta, Philadelphia, and Denver. What do these markets have in common? A simple answer may not be enough as there may be a variety of influences, including but not limited to, demand fluctuations, several consecutive quarters of sustained construction, price pressures from new seniors housing inventory competition or oversupply, lost market share to alternative options for housing and/or care such as age-restricted multifamily apartments, home health services, co-housing, aging-in-place technology, and adverse local economic conditions.

The table below describes the commonalities of each quadrant in the scatterplot chart discussed above for the four-year timeframe. In addition to the assisted living all occupancy rates and average annual same store asking rent growth rates that were diagrammed in the scatterplot chart, stabilized occupancy (defined by NIC as properties that have been open for at least two years or, if open for less than two years, have already reached a 95% occupancy), the percent difference (i.e. “gap”) between the all and stabilized occupancy rates (which denotes the percentage of units still in lease-up), average age of properties in the market, net annual absorption growth, net annual inventory growth, and construction as a share of inventory were examined for each of the 31 Primary Markets to suggest potential patterns for further exploration.

*Source: NIC, NIC MAP® Data Service

Despite the recent softening in assisted living occupancy and rent growth over the past four years, some markets have experienced high rent growth matched with high occupancy, some have seen low rent growth matched with low occupancy, and others have experienced high occupancy and low rent growth, or low occupancy and high rent growth. What are some of the potential connecting factors?

Markets with either (1) strong absorption of new inventory, (2) a lull in cyclical construction, and/or (3) high barrier to-entry markets with limited new stock often have higher occupancy rates and can typically command higher rates of annual rent growth. In contrast, saturated markets—and markets with sustained construction cycles—may experience suppressed rent growth and lower occupancy rates for multiple years until demand catches up with supply. Under such conditions, operators may struggle to attract enough residents to fully lease-up a market’s new and existing units and may react to occupancy pressures by wholesale reductions in asking rents, and/or by offering point of sale concessions to offset and moderate revenue lost to vacancies.

Indeed, this analysis has only scratched the surface. Several questions may need to be answered with further research to understand what the key drivers of rent growth at the market-level are, including but not limited to:

- Influence of market saturation

- Geographic economic conditions

- Staffing costs

- Quantity and quality of existing and new inventory competition

- Availability of alternative options for housing and/or care

- Demographic growth in age- and income-qualified households

- Rising or falling target market income and home values

- Changing resident acuity

- Timing of the construction cycle

- Consumer attitudes and awareness of seniors housing options

- Levels of and duration of rent concessions

- Age of inventory

This commentary has pointed out the wide differences in market performance by occupancy and rent growth and has suggested possible explanations for some of the disparities. However, to more fully understand rent and occupancy performance by market, an exploration of local market conditions and individual market dynamics should be considered.

If you’d like to learn more about the NIC MAP® Data Service, click here to visit our NIC MAP website.

Thoughts From NIC’s Chief Economist

By Beth Burnham Mace

Happy New Year! 2020, the start of a new decade. What will it bring? More seniors that’s for sure. The demographics don’t lie, although the big push is still several years away as the oldest baby boomer doesn’t reach 83 for another nine years. More inventory growth. That’s for sure as well, although the pace of growth may slow in the near term based on today’s starts and projects that have recently broken ground. An economic recession? Well, it appears that the combination of lower interest rates orchestrated by the Federal Reserve, strong job growth, relatively robust consumer confidence, and a modest pickup in global growth may postpone a significant downturn for the time being, allowing the longest economic expansion on record to continue into 2020. However, economic cycles still exist and barring a major exogenous shock to the economy, it is likely that a protracted downturn will occur in the next 24 months.

Happy New Year! 2020, the start of a new decade. What will it bring? More seniors that’s for sure. The demographics don’t lie, although the big push is still several years away as the oldest baby boomer doesn’t reach 83 for another nine years. More inventory growth. That’s for sure as well, although the pace of growth may slow in the near term based on today’s starts and projects that have recently broken ground. An economic recession? Well, it appears that the combination of lower interest rates orchestrated by the Federal Reserve, strong job growth, relatively robust consumer confidence, and a modest pickup in global growth may postpone a significant downturn for the time being, allowing the longest economic expansion on record to continue into 2020. However, economic cycles still exist and barring a major exogenous shock to the economy, it is likely that a protracted downturn will occur in the next 24 months.

Where we live does matter. As we age, where will we want to live? And, as important, how will we want to live? It’s a decision that faces many of us today, either directly for ourselves or indirectly for our elderly parents. In a recent front-page Wall Street Journal story, writer Peter Grant drew attention to and rightfully addressed this question as nearly 13 million older Americans face this decision today and as the massive wave of 72 million baby boomers born between 1946 and 1964 gradually approach the time where post-retirement lifestyle choices will need to be made. Many will prefer to age at home, with technology helping to enable this choice. But many will also prefer to age in a community with companionship, friendship, engagement, involvement, socialization, easy-to-access meals, healthcare, assistance in day-to-day living activities, and importantly safety and security. Cognitive impairment, mobility limitations, multiple chronic conditions and functional restrictions may also cause older seniors to leave their homes for additional care.

Today, there are an estimated 1.6 million units of seniors housing in the United States— which is roughly 18% of households over the age of 80. A recent analysis by NIC suggests that by 2030, 2.5 million units will be needed if that penetration and utilization rate of 18% of households over age 80 is to remain steady in the coming years. For seniors housing operators, this suggests that hundreds of thousands of new units will be needed to satisfy this demand. Even if the utilization rate were to fall below today’s 18%, additional inventory will be needed.

The truth is that the baby boomers have never acted like their parents and always pave a new way forward. It’s likely that new forms of living patterns will emerge. Many of America’s elders will remain in their family homes, many will live in traditional seniors living properties, some will live in an evolving form of seniors living housing that is still emerging, some will live in co-operative living arrangements similar to how they lived during the 1960s, some will live intergenerationally with younger individuals who can help defray costs or help with household chores and maintenance, and some will live in choice-based group homes with their friends like in the Golden Girls sitcom. The truth is that the sheer size of this burgeoning cohort will support many living preferences—within individuals’ existing homes or in communities.

However, the ability to remain at home and continue to be supported by family will be less than today, as another recent NIC study showed that 48% of 75 plus individuals will be divorced in 2029 compared with 39% today. Either due to widowhood or divorce; many will simply not have partners/spouses to care for them. Moreover, the sheer demographics of America are quickly changing the caregiver support ratio, which will fall from seven adult children aged 45 to 64 to care for one parent over 80 years old today to four-to-one in 2030 and three-to-one in 2050. Fewer adult children will live in proximity to their parents as well.

Hence, the desire to live at home may not always be matched by the ability to do so. At the same time, the desire to live in a group setting may not always be matched by the ability to do so. As we consider the aging of our population, we need to think about what America’s elders can afford in terms of their care and housing choices. For example, NIC’s study on the Forgotten Middle, published in May 2019 in the public policy journal Health Affairs, showed that 46% of 75-plus middle-income households will not have sufficient financial resources to be able to live in today’s senior housing.

With a spotlight now shining on the issues of choice, desire, and affordability of care and housing options, we can collectively consider what public and private sector solutions exist today and what needs to be re-imagined, designed, and created. It’s an opportunity for public/private partnerships, as well as for private sector solutions, and innovative and creative public policies.

As always, I welcome your comments and feedback.

Addressing the Workforce Crisis: Labor Management Lessons Learned from a Healthcare Setting

By Ryan Brooks, Senior Principal, Healthcare, NIC

I recently joined the Outreach Team with NIC following a career in acute-care hospital and ambulatory operations with a large academic medical center. My previous focus was on patient throughput strategies, EHR optimization, telemedicine implementation, value-based care, and lean deployment throughout our organization. I join NIC in the hope of bringing a perspective on how hospitals and health systems can collaborate with the senior housing and skilled nursing sector to increase value, improve care, and ultimately provide a better patient experience. With the implementation of CMS’ Patient Driven Payment Model, I am also able to serve as an expert in industry transition to quality-based reimbursement.

I recently joined the Outreach Team with NIC following a career in acute-care hospital and ambulatory operations with a large academic medical center. My previous focus was on patient throughput strategies, EHR optimization, telemedicine implementation, value-based care, and lean deployment throughout our organization. I join NIC in the hope of bringing a perspective on how hospitals and health systems can collaborate with the senior housing and skilled nursing sector to increase value, improve care, and ultimately provide a better patient experience. With the implementation of CMS’ Patient Driven Payment Model, I am also able to serve as an expert in industry transition to quality-based reimbursement.

As senior housing becomes further ingrained in the care continuum, I believe that we can meet the needs of all seniors, but to do so will require skillful cooperation and coordination among all who play a role. I hope to bring a unique viewpoint to our team and share many of the valuable lessons I learned throughout my tenure in hospital administration. It is in that vein that I share my first post, one that focuses on employment retention and workforce engagement strategies.

Retaining an engaged workforce is a cornerstone of long-term business success, but doing so is not always an easy task. Generational preferences and rising wages across the country mean managing labor, and its associated costs is a growing concern for all businesses. According to NSI Nursing Solutions’ 2019 National Health Care Retention and RN Staffing Report, the average cost of turnover for a bedside nurse is anywhere from $40,300 to $64,000. It’s also widely recognized that turnover often leads to declines in safety, quality, and experience. Strategies designed to establish consistent labor pipelines and enhance the quality of staff may help mitigate these challenges. While some of the strategies discussed below in this commentary are specific to healthcare, others can be utilized in any setting. As is often the case, these strategies will require an upfront cost, but with a successful implementation, that cost can be recouped over time as employee turnover, recruitment, onboarding, and training costs greatly outweigh the initial investments.

Attract and Develop Talent Using Residencies & Training Programs

Getting new staff in the door is one of the biggest challenges currently facing health systems. With experienced clinicians commanding increasingly high salaries and generous benefit packages, attracting an early-career talent pool which can be trained to the standards and practices of a specific facility is a winning strategy. Traditional physician residencies have been around for more than a decade, but increasingly residencies and training programs are being made available for a wide variety of clinicians, including nurse practitioners, physicians assistants, registered nurses, certified nursing assistants, and clinical technicians.

Residencies can provide a win-win for both the organizations seeking staffing and the employees looking to grow professionally. Access to training in a real-world care setting, the expertise of physicians, and continuing education opportunities can set up an organization with a pipeline to deliver quality clinicians at a more affordable cost. Graduates of these programs are better trained and therefore, better equipped to find employment, but they also establish roots during training. These roots—relationships, routines, and familiarity—often lead to a high retention rate following graduation from the program. It can be rewarding to train the next generation of quality clinicians, but for employers the ultimate goal is securing access to a deep pool of skilled talent.

Create Growth Opportunities for Long-Term Retention

All employers would like their employees to feel a sense of accomplishment in their work. However, employers often seem to fail their employees when it comes to the intrinsic satisfaction they feel. Senior staff with organization-specific expertise can grow frustrated when their organization adds new staff with the same titles and job descriptions they earned over years of service, for example. Even happy employees look for better opportunities, and often these employees are the ones that organizations most want to retain. Employers cannot overlook giving their employees a reason—beyond a paycheck— to stay with the organization.

Career ladders can both reward senior staff for years of service and allow for recognition of skill sets with additional compensation. Procedural skills, certifications, and the ability to staff various care areas should be built-in prerequisites in an organization’s career ladder. With careful design, the career ladder is a powerful tool, enabling organizations to encourage retention, raise average experience levels, and incentivize ongoing professional development.

Invest in Training for Organizational Success

Another often overlooked retention incentive is to invest in training and ongoing development. This strategy requires upfront investment, but can yield improved billing and reimbursement, as well as improved patient care. Take the recent implementation of CMS’ Patient Driven Payment Model and the impact it has on mental health treatment as an example. Only about 5% of nursing home residents have a diagnosis of depression, but academic studies indicate the prevalence is closer to 40 %. The disconnect in depression identification in this population can partly be attributed to the differences between overburdened frontline caregivers with multiple pressing demands and the highly-focused nurse teams that conduct studies specifically for academia. Another contributing factor is that the methodology of identifying depression, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), relies on self-reporting that can be distorted by the respondent’s perception of the situation.

With PDPM, however, operators are rewarded for treating each resident’s specific needs, with payments increasing in line with patient acuity. This incentivizes depression identification and documentation, as payment boosts can bring in additional reimbursement income. Offering frontline staff training and education on how to identify and treat depression yields benefits in terms of staff satisfaction—and also improves resident outcomes and a facility’s bottom line.

Avoid Single-Site Employment Models

Absences and call-outs are a reality facing any organization. Those absences are typically resolved using on-call staff or bringing in an unscheduled employee at a premium rate of pay. For employers with multiple sites in a specific region, creating an employment vehicle that allows for flexibility with regards to daily work location can be a strategy to avoid costly premium wages that are often used to fill holes in schedules. Additional incentive payments made to employees willing to work at multiple sites can be recovered by avoiding the costly alternative of overtime or on-call pay. Navigating Human Resources hurdles is the most challenging aspect of this strategy, as titles, benefits, and job responsibilities often vary slightly from one site to another. Usually, developing a separate employment intermediary that houses these flex-staff can resolve those challenges.

Amidst accelerating wage growth, persistent workforce shortages, and other labor-related challenges, the pressure to implement creative, evidence-based solutions to prevent shortfalls both in daily staffing and longer-term leadership roles is intensifying. Employing some—or all— of the strategies mentioned here will help organizations better positio themselves for greater long-term success.

Scholarship Program Encourages Industry Careers

NIC’s Fall Conference is known for convening seniors housing and care experts to discuss the future of the industry, but there’s a lesser known group of attendees poised to play a role in carrying the industry even further into the future—the NIC Scholars. As part of the NIC Scholars program, NIC offers conference scholarships for both its yearly conferences to a small number of nominated and qualified college students.

Given the expanding need for talent and innovation in the sector, NIC views this scholarship program as an important part of its mission to support access and choice for America’s seniors. Participating in the conference offers students the chance to deepen their understanding of the challenges and opportunities in seniors housing and care while making connections with current participants in the industry. Following the conference, students amplify their learnings by sharing with fellow students and professors back on campus.

Fourteen students attended the 2019 NIC Fall Conference as part of the NIC Scholars program, representing undergraduate and graduate programs across the country including Columbia University, Cornell University, George Mason University, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, University of Texas at San Antonio, University of Wisconsin Eau Claire, and Washington State University.

We sat down with five of these scholarship recipients to learn more about their experience at the conference and their motivations for pursuing careers in seniors housing. If these students are any indication, the future of seniors housing is bright.

(Left to right) Ali Siddiqui, Eduardo Cano, Trent Segers, Dan Gardner, Bradley O’Neil

As a whole, the students agreed that the NIC Talks offered during the conference were tremendously inspiring. They appreciated hearing perspectives from forward-looking and innovative thinkers on filling needs in the seniors housing and care space. The group also valued the opportunity to meet industry executives and attend presentations on the latest trends impacting seniors housing and care.

New Ideas, New Perspectives

Bradley O’Neil, a second year MBA student at the University of Texas at San Antonio with a real estate finance and development concentration, became interested in seniors housing when a professor opened his eyes to the opportunities available in the industry. O’Neil noted that the industry isn’t as well known by students considering a career in real estate. His original goal was to pursue multifamily development, but he saw the appeal of Seniors Housing after learning more. “We have a chance to get our foot in the door and really have an opportunity to grow within the industry and make a career out of it long term.”

O’Neil observed that the industry will need a lot of creative thinking as it moves into the future and that industry attendees at the conference were welcoming to the students. He mentioned one attendee telling him, “We need people like you around. We need new thoughts, new ideas, new perspectives.”

Inspired by the Residents

Dan Gardner, a second year MHA student at Cornell University, developed an interest in the seniors housing industry during a part-time job in high school. “When I was 16, I went to work in a nursing home. It was really hard, but I loved the relationships with the residents and the people I met there.”

Gardner has an entrepreneurial background and sees the seniors housing industry as ripe for innovation. He is developing unique assisted living concepts and, through a connection he made at the conference, has plans to meet up with an operator to tour a community on the west coast.

Like his NIC Scholars peers, Gardner appreciated meeting other students pursuing careers in this industry. He found it “comforting and inspiring to be around like-minded students and professionals.” He mentioned that few of his classmates are considering this industry and expects to stay in touch with fellow NIC Scholars as they begin to grow their careers.

Enabling Technology

Trent Segers, a full-time MBA student at the University of Texas, will graduate in May with plans to pursue “enabling technology” in the seniors housing space. Segers has experience launching a technology-based tool for senior living communities and came to the conference to look for inspiration for other business ideas.

Inspired by his relative’s stay in a skilled nursing facility, Segers saw an opportunity to use technology to improve the residents’ experience. He noted that in conversations with conference attendees about industry pain points, the need for efficiency was a key theme. Segers believes that in a labor-intensive industry like seniors housing and care, opportunities lie in increasing efficiency through technology to augment what nursing and other staff are doing today.

Internship Learnings

Ali Siddiqui, pursuing a dual degree MBA and master’s in real estate at Cornell, hopes to work in real estate finance.

While interning with a large operator last summer, Siddiqui learned that senior living operations are more challenging than one might expect. He noted the hospitality component of seniors housing and said that not everyone realizes how much healthcare and cost of care come into play.

Siddiqui saw the conference as a hallmark event. “If you want to be in the industry for seniors housing and you want to meet operators and other players—debt lenders, finance, equity—this is the conference to go to.”

Operators are Key

Eduardo Cano, in his second year at Columbia Business School, plans to pursue a consulting career in real estate private equity.

The conference highlighted for him how different stakeholders in the seniors housing market analyze properties. Cano mentioned learning “how important the operator is in the success of one of these facilities.” Cano is interested in exploring how the on-demand economy can be leveraged to meet the needs of seniors.

The NIC Scholars left the conference with increased enthusiasm for joining the sector and an appreciation for the lasting connections they made there.

While NIC Scholar nominations are already closed for the upcoming 2020 NIC Spring Conference, any university or college that is interested in nominating scholars for future NIC Conference Scholarships, please contact Cathy MacKenzie at cmackenzie@nic.org to join NIC’s list of participating schools.