A Note from Ray Braun

I am excited to serve as NIC’s president and chief executive officer at a time when the senior living sector is experiencing unprecedented change. Opportunities to increase access and choice are rapidly emerging as millions of baby boomers age and focus on wellness and enhanced lifestyles. We are seeing this in the growth of active adult properties, in more cost-effective housing and care solutions for “middle market” seniors, and in innovative partnerships with payers that assume residents’ healthcare risk to improve their care and clinical outcomes. It is my privilege to help owners, operators, investors, and partners successfully navigate this challenging landscape!

I am excited to serve as NIC’s president and chief executive officer at a time when the senior living sector is experiencing unprecedented change. Opportunities to increase access and choice are rapidly emerging as millions of baby boomers age and focus on wellness and enhanced lifestyles. We are seeing this in the growth of active adult properties, in more cost-effective housing and care solutions for “middle market” seniors, and in innovative partnerships with payers that assume residents’ healthcare risk to improve their care and clinical outcomes. It is my privilege to help owners, operators, investors, and partners successfully navigate this challenging landscape!

I look forward to collaborating with you to improve the health and wellbeing of seniors and mitigate the increase in healthcare costs jeopardizing access and choice to senior housing and care. Together, we can ensure access and choice among senior housing options and improve healthcare outcomes and the quality of life of seniors in the United States. I can’t wait to see the impact of our journey!

Sincerely,

Ray Braun

President & CEO, NIC

Harrison Street Embraces ESG Investing: A Conversation with Jill Brosig

It may seem like a big jump from physics to senior housing, but not for Jill Brosig. She started her career at a national research laboratory designing a system for a particle detector to eliminate four tons of Freon emissions leaking into the atmosphere every year. Flash forward, and Brosig is still on a mission to better the environment but in a much-expanded role. As Chief Impact Officer at Harrison Street, a big senior housing investor, Brosig oversees the measurement, management, reporting and enhancement of the firm’s Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) initiatives. NIC’s Chief Economist Beth Mace recently talked with Brosig about ESG, Harrison Street’s approach, and how ESG is impacting the senior living industry. Here is a recap of their conversation.

It may seem like a big jump from physics to senior housing, but not for Jill Brosig. She started her career at a national research laboratory designing a system for a particle detector to eliminate four tons of Freon emissions leaking into the atmosphere every year. Flash forward, and Brosig is still on a mission to better the environment but in a much-expanded role. As Chief Impact Officer at Harrison Street, a big senior housing investor, Brosig oversees the measurement, management, reporting and enhancement of the firm’s Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) initiatives. NIC’s Chief Economist Beth Mace recently talked with Brosig about ESG, Harrison Street’s approach, and how ESG is impacting the senior living industry. Here is a recap of their conversation.

Mace: Can you please tell us about yourself and your role at Harrison Street regarding ESG.

Brosig: My team oversees the company’s ESG activities. Four of us work on ESG at our Chicago headquarters. We also have a team member in Canada, and we’re adding someone in Europe. Harrison Street has had a formal ESG program since 2013, but my role started in January 2020 when it was decided that we needed a fulltime ESG staff. Prior to that, ESG was handled through committees and consultants. Now we have a dedicated Impact Department. We still have committees with executives who are very involved. ESG is only powerful if it is embedded in how we do our business.

Mace: How did you personally get involved in ESG?

Brosig: I don’t have a real estate background. My background is in physics. I’ve been at Harrison Street since 2008 in a number of different roles. But my background specific to ESG actually started when I was an intern at Argonne National Laboratory in the Chicago area. My first assignment was to fix the Freon leak, and it felt good to help the environment. After I graduated with a physics degree, I did research on inertial confinement fusion. Fusion is how the sun makes energy, a process that could potentially be a perpetual source of energy that is clean and reliable. When I was hired at Harrison Street, I helped our operating partners improve their businesses. On the social side, I taught a class on how to market to women and reached 3,000 people. A lot of decision makers in the senior living selection process are women. I later worked on a project to create perfect power—power that is not just clean but also safe and reliable. I was thrilled to be named the company’s first chief impact officer which coincided with Harrison Street’s 15-year anniversary. Our CEO, Christopher Merrill, came out with a tagline, “Making an Impact.” A big part of what we do is to tell the story of what we’ve done to impact the world, such as creating jobs or introducing new technology to take better care of our residents.

Mace: How do you define ESG at Harrison Street?

Brosig: We don’t define ESG any differently than anyone else. ESG stands for Environmental, Social, and Governance. Companies are more focused on environmental initiatives because it is easier to measure. Buildings with LED lighting, low flow water fixtures, and better mechanicals have lower expenses which are reflected in lower utility bills. The social piece is more difficult to define and measure. We are actually conducting research and talking to key stakeholders to identify the critical elements of the social portion. Every three years, we conduct a materiality survey to ask our stakeholders what is most important to them from an ESG perspective. Historically, the responses have been granular, focused on how to make buildings more efficient. But last year, the responses had a more macro perspective. Stakeholders were concerned about climate risk and resiliency. They saw the fires in Australia, flooding in Germany, and the partial collapse of a condominium building in Florida. They wanted to know whether their investment was going to be resilient depending on what Mother Nature would throw at it. That was number one. Second was the question of carbon emissions. How are we ensuring that we are not contributing to climate change? What are we doing to reduce our carbon footprint? The other issue that scored high on the survey concerned the health and wellness of our building occupants. We can provide a building that is net zero of carbon emissions and resilient to weather events. But if we haven’t thought about the human element then the building is just an empty shell. We came out with our Climate Action Plan on our website to address these issues. We’re very specific. We have a 2025 goal to reduce our carbon emissions by 70%. On the social side, we have identified at least a dozen different elements that matter to us and our stakeholders. Governance includes a lot of reporting. We try to be transparent about what we’re doing and how we’re performing. Every year since 2014, we’ve issued a Corporate Impact Report which is posted on our website.

Governance also includes diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). We want to make sure everyone has the opportunity to advance, and that our hiring and development practices continue to support that. We have a wonderful recruiting process, so we have a diverse slate of candidates to build a pipeline of team members and executives with varied backgrounds.

Mace: How do E, S and G relate to senior housing?

Brosig: The environmental aspect of senior housing is about the same as it is for other types of buildings. But there are some things we are doing in terms of lighting related to seniors. As people age, their eyesight may not be as sharp, or they may have a visual impairment. We are working with Well Living Lab, a research center, to understand the interaction between human health and well-being and indoor environments. We’re doing field studies to see if we can optimize lighting in senior living properties to help residents improve their sleep, cognitive health, productivity, and general wellness. We’ll also be looking at indoor air quality, thermal comfort, and other aspects of indoor spaces across the spectrum of senior living property types. As I mentioned, governance covers a lot of reporting and transparency. The social impact is where senior housing can really outstep the other asset classes. The challenge is how to capture the impact and tell the story. We’re the fifth largest owner of senior housing and have so many partners. We bring them together once a year so they can share best practices, discuss new technologies and the problems they face. I love working with our partners. They are not in competition with each other. We are not running out of elders. The real competition is the home. So how do we work together to create a more attractive product? That’s what I love about ESG. It’s about collaboration not competition. We also have to consider the staff. We decided to pursue Fitwel certification, the healthy building initiative, for all our occupied assets. But there was no scorecard for senior housing. So, we worked with the Center for Active Design, who administers the Fitwel product, to create a scorecard that did not compromise or diminish the intent of the original scorecard. The challenge was that we were creating a scorecard for two populations: the staff and the residents. We think holistically about both groups.

Mace: What is the ESG business proposition?

Brosig: ESG is a win-win situation. There are financial benefits for doing the right thing. The challenge is to demonstrate that ESG is bringing additional value, whether it’s faster lease-ups, longer tenure by staff and residents, or a building that is more valuable at the time of sale because of ESG activities. We have been told by certain buyers that, if you don’t have an ESG story at your property, they will not be interested. It’s what investors are starting to demand. They want a building that is good for the environment with social programs that are good for the community. That’s the differentiator that creates value.

Mace: Where is senior housing on the spectrum for ESG relative to other commercial real estate products?

Brosig: I can’t speak for other commercial real estate products as we have not generally focused on investing in traditional property types. Nevertheless, senior housing has an advantage on the social piece but needs to do more to tell its story. All building operators are becoming more focused on the environmental piece because energy expenses are becoming a bigger and bigger part of the operating budget. Some jurisdictions have stricter building codes for new construction. But a lot of our partners are not waiting for municipalities to tell them what to do. They are designing for the future.

Mace: What are the benefits to incorporating ESG principles into senior housing? What are the challenges, risks, and costs?

Brosig: On the environmental piece, we know that replacing light fixtures with LED lighting and installing low-flow water fixtures produces a quick return on investment. For many properties, on-site solar systems are a worthwhile investment. Looking at reducing waste to landfills are great projects as well. In addition, we are rolling out electrical vehicle (EV) charging stations. Not everyone will be driving EVs, but we know it’s coming. We are piloting close to 300 EV chargers at our senior and student properties. Depending on the property, it can be added as an amenity or revenue source. This type of project will allow us to measure avoided carbon emissions. Together all these types of initiatives form a comprehensive response to how we are running more efficiently while also saving money.

Mace: How do you track ESG at Harrison Street for senior housing?

Brosig: Our Corporate Impact Report and Climate Action Plan are publicly available on our website. We track how many seniors we’ve cared for and update that every quarter. We track how many jobs we’ve created by investing in senior living communities. On the environmental level, we track our buildings’ carbon footprints, utilities and energy usage, and wastewater management.

Mace: Providing housing and care to America’s Forgotten Middle group of seniors is challenging. In 2019, NIC provided a grant to NORC at the University of Chicago to study the middle-income senior cohort and found that 14.4 million Americans would fit into this category in 2029. A recent update of this study puts this estimate even higher. If lower returns were required to provide care and housing to this cohort, do you think that large pension funds could forgo some level of return in exchange for the social good of providing housing to this much needed cohort of seniors? Many of this cohort are today’s teachers and public servants, the very constituents that many pension funds serve.

Brosig: We have to figure out how to craft a product that fits the middle-income senior cohort but is on par with returns from the higher end product. Investors, especially pension funds that are fiduciaries, want both. Technology is part of the answer. We can make buildings smarter with technology to create a better performing product. Technology can help monitor residents and relieve workers of administrative tasks to possibly reduce costs. Are there other ways to reduce labor costs? We have to find a way to create a financially sound product that competes with other investments. As an industry, we have to think differently.

Boomers, Employees, Expenses, and Margins: CEOs Tackle the Big Issues and Look Ahead

Providing an insightful take on today’s senior living climate, four high-profile CEOs shared their big-picture perspectives during a panel discussion at the 2022 NIC Fall Conference. The Conference was held September 14-16 in Washington, D.C., drawing more than 2,800 attendees.

Providing an insightful take on today’s senior living climate, four high-profile CEOs shared their big-picture perspectives during a panel discussion at the 2022 NIC Fall Conference. The Conference was held September 14-16 in Washington, D.C., drawing more than 2,800 attendees.

The CEOs highlighted the industry’s need to adjust its approach to the next customer base—the baby boomers—who expect a different kind of product and a lot of service. Occupancies, rising expenses, and the labor shortage are big concerns. But the CEOs see technology and reinvestment in their communities as the best path forward to success.

NIC Board Chair and panel moderator Kurt Read kicked off the discussion. “Who is our consumer today? Who is our future consumer?” asked Read, managing director, RSF Partners. “Are they different?”

The CEOs agreed that the next generation of senior living residents, just now starting to arrive, are quite different from today’s customers, mostly from the silent generation, a cohort focused on service and modesty.

“Baby boomers don’t live in a world of need,” observed panelist Brenda Bacon, president & CEO, Brandywine Living. “Boomers live in a world of want.”

Bacon explained that baby boomers like to be indulged and don’t want to be told what they need. Marketing messages should showcase senior living offerings as a choice that baby boomers are making for themselves. “We need a whole different set of services and language to talk to boomers,” said Bacon.

Technology will play a big role for the next wave of consumers, according to panelist Cindy Baier, president & CEO, Brookdale Senior Living. Baby boomers, and their families, expect buildings equipped with the latest technology. “We have to step up our game,” said Baier.

The pandemic pushed technology forward quickly, said panelist Sevy Petras, CEO and co-founder, Priority Life Care. Telehealth became more widely available. The lockdowns necessitated the innovative use of technology to keep families and their loved ones in touch.

Market Segmentation Under Way

Moderator Read asked whether senior living is undergoing a segmentation similar to that of the hospitality market where different types of hotels serve different consumers and price points.

Segmentation of senior living is already under way, the CEOs agreed. For example, Priority Life Care focuses on the middle market, while Brandywine targets the luxury segment. Brookdale, the nation’s largest senior living operator, concentrates on the local customer base of each property, both middle market and high-end.

Panelist Greg Smith noted, “All product segments are growing because demand is growing.” Smith is president & CEO at Maplewood Senior Living, which serves the luxury market.

The immediate focus of the CEOs is to rebuild occupancy, curb expenses, and navigate the labor shortage.

Operators are juggling the need to attract customers with attractive pricing just as expenses are rising quickly. Even so, rate hikes of 7-10% are common and consumers aren’t pushing back just yet. Brookdale’s Baier thinks operators should have pricing power as long as new construction remains muted.

Moderator Read suggested that the industry should adopt “radical transparency.” He again pointed to the example of the hospitality industry that implemented a standard chart of accounts along with data sharing which led to new capital formation and “stunning innovation.” The panelists agreed more transparency among providers would help boost the industry.

The labor issue is a top priority for the CEOs. “My number one focus is my employees and to create opportunities for them,” said Petras. “If we take care of them, they will take care of our residents.”

The CEOs discussed various approaches. The creation of career paths along with stepped up training programs and recruiting efforts were mentioned. A creative idea is to have family members volunteer at the community, though the CEOs said that would present liability issues.

Scale Up

As an investor, Read suggested that some scale of assets is needed to attract top management talent and smooth out returns. With interest rates and the cost of capital rising, Read asked what the industry is doing to increase returns.

Baier said that margins will take a while to recover. She thinks the effective use of technology will help make senior living services more affordable. “That has to be part of the answer,” she said. Baier added that senior living, in general, lags behind other industries in the adoption of new technology and needs to catch up.

Read asked what the CEOs would do if they had $1 million of free cash flow to spend.

Maplewood’s Smith would put the money into operations and reinvest capital in the real estate. Brandywine’s Bacon would create more big units to meet the demand. Baier at Brookdale would use the money to reduce contract or agency labor in the buildings.

Petras said, “Every single penny would go to support the employees.” She specifically mentioned using the money to support childcare costs, transportation, and tuition reimbursement. The other CEOs agreed that investing in employees was key. “We need to create environments where people want to work,” said Smith.

Read concluded the discussion by noting that 80% of senior living customers are women and 80% of the caregivers are women. “How are we doing on diversity?” he asked.

The CEOs said more needs to be done. Bacon noted that the industry doesn’t have enough diversity of color or gender. Also, residents are typically white, and the workers are people of color. “That picture says something,” she said. Bacon thinks it’s important to promote from within and attract younger workers. “We have a lot of work to do,” she said.

Petras said owners and operators need to collaborate and conduct more media outreach to show the opportunities offered by the industry. Senior living not only provides a paycheck but also a purpose. But, she added, “The industry has to do this together.”

NIC is working with its industry partners on the Senior Living DEIB Coalition to support diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives. NIC has also formed a DEI committee which is chaired by Brookdale’s Baier. “We need to reach out to make everyone be their best selves in senior living,” she said.

Putting the “Active” in Active Adult

During the 2022 NIC Fall Conference session, “Rational Exuberance: Investing in the Rapidly Growing Active Adult Segment,” Kathleen Ryser, senior director of Seniors Housing Lending at Freddie Mac, recalled this about first entering the segment: “The first thing that became a challenge for us was figuring out how to define active adult.”

During the 2022 NIC Fall Conference session, “Rational Exuberance: Investing in the Rapidly Growing Active Adult Segment,” Kathleen Ryser, senior director of Seniors Housing Lending at Freddie Mac, recalled this about first entering the segment: “The first thing that became a challenge for us was figuring out how to define active adult.”

She’s not alone. The term “active adult” has been used for years to identify the emerging property type rapidly gaining attention and popularity due to the coming wave of demand from aging baby boomers.

In spite of the hype around active adult properties, there was no unified definition until recently.

In September, NIC released a white paper on the emerging active adult rental segment. It is intended to fill the void in the market and provide stakeholders with critical information about what this property type is and what older adults are looking for. Clearly defining active adult rental properties enables better data collection on the growth and performance of the segment, which supports the transparency investors need to ultimately provide greater access and choice for older adults.

What Classifies as Active Adult?

Active adult rental properties are age-eligible, market rate, multifamily properties that are lifestyle focused, with general operations that do not provide meals.

‘Younger’ older adults with active lifestyles are increasingly seeking the vibrant, modern, and with lower acuity health needs attributes of active adult rental properties. These baby boomers want social opportunities like regular Thursday evening happy hours or a Tuesday morning golf league at a nearby course. Active adult communities fill a market need by giving residents an option that lies somewhere between conventional multifamily housing and traditional senior living options.

To clarify what active adult rental properties are, we’ll dive deeper into three components of the property type definition.

1. Age-eligible: The property must restrict residents based on age. This typically means at least one resident in the household must be 55+, 62+, or 65+, depending on the local governing jurisdiction.

Prospective active adult residents are looking for a community of peers, so the age restricted component is often attractive. The average age of residents at move-in is in the upper 60s to low 70s—which currently perfectly aligns with the early edge of baby boomers.

However, “age creep” has often been a concern related to active adult communities. At the NIC Fall Conference, one audience member asked if panelists experienced age creep, and if so, how they dealt with it.

Jackie Rhone, executive director of Real Estate for Active Adult at Greystar, said that the average age of their active adult residents decreased from 76 to 71. One factor was the pandemic: a lot of older adults experienced solitude and loneliness when they were unable to see friends or family, so many sought communities with built-in social connections.

Another audience member asked if active adult would replace independent living in the next 10 years, to which all panelists commented on that all-important age difference. The average age of an independent living resident is 82-83—at least 10 years older than the average active adult resident. They are understood to be completely different consumers, with differing health and mobility needs, so panelists agreed that both housing types are needed in the market to ensure older adults have options. More details on the differences between active adult and independent living residents can be found in the white paper.

2. Multifamily: The definition excludes single-family home-only communities (SFH). Similar to the senior housing data collection, it would, however, include data on attached or detached SFHs within communities with majority multifamily dwellings.

Panelists at the NIC Fall Conference discussed at great length whether active adult was more similar to senior housing or to multifamily housing.

Joe Fox, co-founder and co-chief executive officer of Livingston Street Capital, called active adult a “tweener.” He said the way you market active adult is more akin to senior housing, but the way you operate it resembles multifamily. The white paper further compares the two segments.

Rhone assembled a team dedicated solely to marketing and leasing active adult properties, and Greystar created a specific training program to teach active adult salespersons about the unique wants and needs of the kinds of consumer who seek to live there. Rhone believes there must be special attention paid to differentiating active adult from multifamily, so the Greystar team takes time to educate the consumer, their family, and the market about what an active adult community is and the benefits it has for residents.

3. Meals not included through property operations or base rent: The definition does not include properties that provide lunch or dinner or allowances/credits for meals. Active adult rental properties may, however, provide more nominal offerings such as continental breakfasts or happy hours.

Active adult renters are not looking for amenities like meal service. What they desire is laid bare in the name itself: opportunities to be active in their new community. “As an operator, you are selling a lifestyle, not a home,” said Fox. Rhone echoed the sentiment: “I’m not selling four walls. What’s driving them is a lifestyle. That is what keeps them there.”

Residents choose to live in active adult communities because of the vibrant activities program—shuffleboard and bingo won’t satisfy this cohort. They are looking for more sophisticated, edgy, and unique social offerings, like wine tastings, book clubs, or Top Golf memberships. They aren’t entering the community for the actual space—rather, for the community, friendships, and activities it provides.

Monitoring the New Property Type

Millions of baby boomers will soon be considering their housing options going forward, and a growing number of them with lower acuity health needs prefer an active, community-based lifestyle lived alongside generational peers. In order to adequately provide access and choice for these seniors, data will enable more transparency.

Though data collection of this emerging property type is still in its nascent stages, with NIC’s new definition, NIC MAP Vision is collecting segment-specific data allowing potential investors and other market stakeholders to access data on the characteristics and financial performance of more than 500 active adult properties across the country. NIC MAP Vision plans to produce more robust data, including operational performance and additional property coverage, by early 2023.

This new common understanding of active adult will better enable data collection on the growth and performance of the sector, which investors seek to strategically capitalize this housing segment and to provide older adults the housing and care options they need.

Skilled Nursing Transaction Pricing Continues to Edge Higher

by Bill Kauffman, Senior Principal, NIC

Pricing for skilled nursing properties has held up in the past two years despite some negative headlines and weak, albeit improving, market fundamentals. Investor interest by private buyers has dominated the transaction landscape. This article delves into various reasons why this has been the case and why this could change in the months ahead.

Pricing for skilled nursing properties has held up in the past two years despite some negative headlines and weak, albeit improving, market fundamentals. Investor interest by private buyers has dominated the transaction landscape. This article delves into various reasons why this has been the case and why this could change in the months ahead.

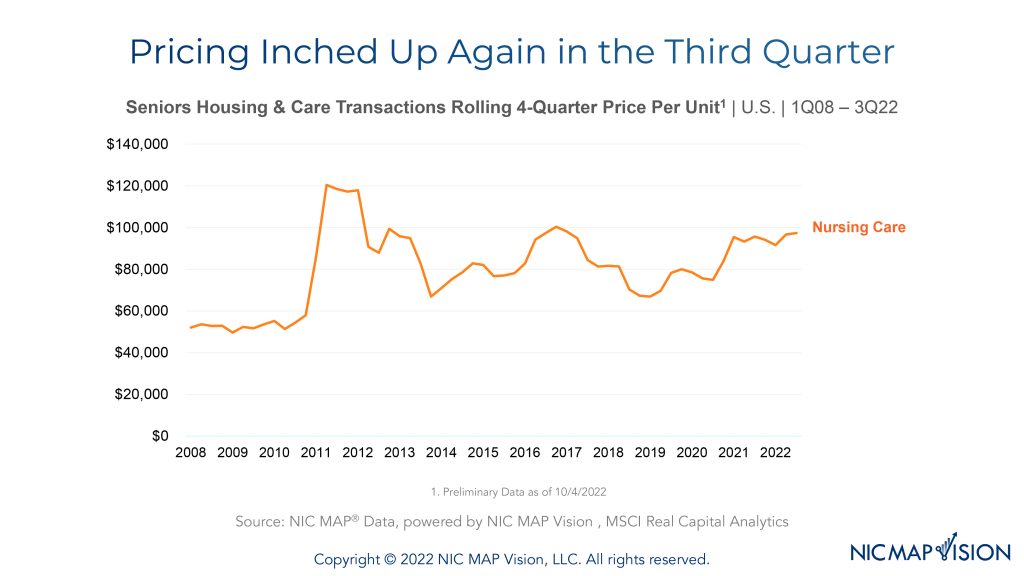

For context, the chart below shows the historical trend of property pricing per nursing care bed. (Note: The data represents properties that have traded and does not include pricing of properties if they have not been transacted in the time periods shown. Hence, the mix of properties will impact the average prices reported). In late 2019, the price per nursing care bed averaged $80,000 before slipping 1.8% to $78,600 in the first quarter of 2020. Due to the pandemic, pricing declined another 4.6% to $74,900 in the third quarter of 2020, its pandemic low. The decline made sense at the time because many properties were struggling during the pandemic due to low census counts, staffing challenges, regulatory requirements, and other factors.

However, the price per nursing care bed remarkably increased 27.4% to $95,400 by the first quarter of 2021 during a period of very low occupancy levels. Since then, occupancy has partially increased from 74.0% to 79.3% but remains challenged with 7.1 percentage points of recovery required to get back to pre-pandemic levels. Nevertheless, the price per bed averaged $97,300 as of the preliminary data for the third quarter. This was 21.6% above the level in the fourth quarter of 2019 before the beginning of the pandemic.

At the same time, there are headwinds against higher prices. These include the risk of Medicare reimbursement cuts, low occupancy rates, chronic underfunding of Medicaid reimbursement in many states, a staffing crisis, and ongoing elevated inflation including wage rate growth. Given the challenges that are present, why has the nursing care property price per bed increased?

There is not simply one answer as to the reason behind why skilled nursing price per bed is relatively high, especially considering the challenging operating fundamentals. There are likely many factors involved. These include strong private buyer interest, compelling demographic trends favoring the necessary care required for aging adults who have higher acuity needs as well as their more complex medical needs, changes in capital and debt markets, financial support from the federal government during COVID, and other factors and trends. Below, I discuss each of these conditions.

First, the low interest rate environment fostered by the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic created a tremendous amount of liquidity and pushed investors into a risk-taker environment. As a result, most asset prices including real estate and public equities, increased significantly during the height of the pandemic. Furthermore, the government made a commitment to financially support the skilled nursing industry during the pandemic. This was evident by many Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans, Medicare prepayments, Medicaid rate increases, and other forms of aid at the state levels. Second, the Patient Driven Payment Model (PDPM), implemented before the pandemic, can compensate for higher care levels unlike the previous model (RUG-IV). Thus, PDPM has the potential to create higher cash flow for operators of skilled nursing properties. Buyers can justify paying higher prices per bed if they are estimating higher cash flow.

Second, owners with more properties can benefit from scale in certain geographies and potentially experience other benefits like staffing flexibility. Therefore, some owners have planned to grow by acquisition and can justify higher prices paid if they own more properties in a defined geographic area. Another potential reason is the opportunity for growth in other ancillary businesses, such as in-house dialysis, contract therapy, wound care, pharmacy services or an on-site diagnostic lab. Also, there is the dynamic that there are more buyers than sellers of skilled nursing properties, at least for now.

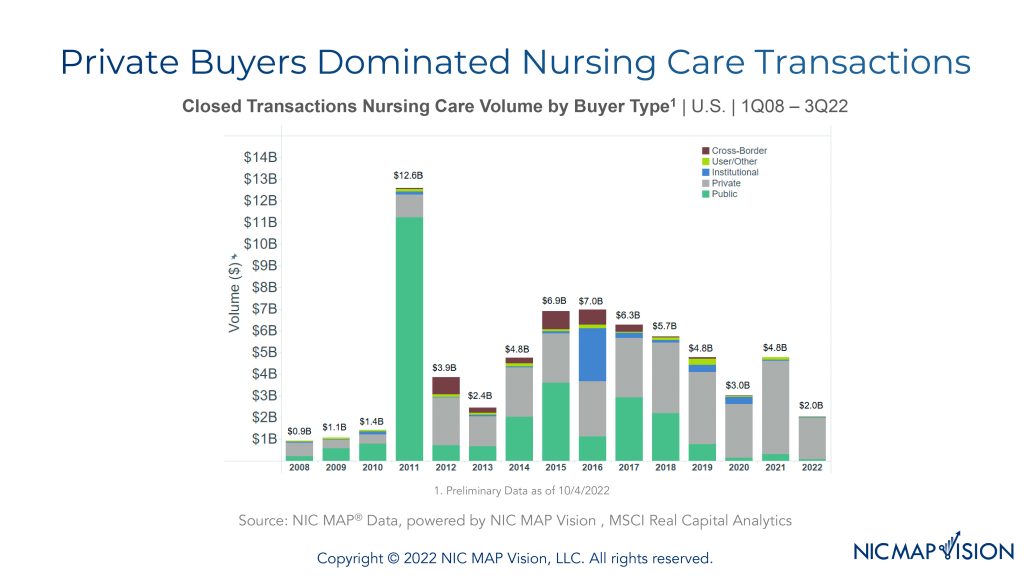

Private buyer interest in skilled nursing properties has dominated the transaction market for the past few years. Specifically, over the past three years the industry has not only seen the private buyers dominate the transaction market, but the percentage of closed transactions attributed to these buyers has steadily increased. Through the third quarter of 2022 private buyers represented 94% of buying activity, in 2021 they were 90% of activity, and in 2020 closed transaction dollar volume attributed to the private buyers was 82%. This activity has contributed to higher prices as these buyers bid up prices to win the deals.

Furthermore, many investors view higher acuity patients as an opportunity for their business model. As mentioned earlier in this article, the Patient Driven Payment Model (PDPM) creates the potential for operators to receive additional payment for higher acuity patients, and perhaps higher cash flow of which many investors/owners find attractive. Particularly, PDPM reimburses skilled nursing facilities based on the medical complexity of patients rather than the RUG-IV model based on volume of services provided. This model may impact the resident profile as many operators could move toward a higher-acuity patient profile. Investor interest is likely to continue given the favorable demographics regarding the growth of the older adult population and the expected need of many within this population to require 24-hour care because of multiple chronic illnesses as they age.

Lastly, there is a yield spread differential in nursing care properties compared with other real estate property types. For example, if skilled nursing properties are selling at 12% cap rates, there is still positive leverage and there historically has been significant cushion if the cost of debt capital is, for example, in the 6% range and combined loan-to-value ratios were in the 85-90% range for a stabilized property. In many other real estate property types, leverage has turned negative with the cost of debt exceeding cap rates, which are rising in today’s economic environment. In addition, from an overall real estate investment perspective when measured against other real estate asset types, 12% cap rates look very attractive. Cap rates for office have been in the range of 6-7%, for example, and in the range of 4% for multifamily. However, this specific appeal could certainly change if interest rates continue to increase rapidly and stay elevated for longer.

Skilled nursing property pricing has been stronger than many would have expected during these challenging times for various reasons. However, the risk of higher interest rates and labor market challenges could provide additional reasons for sellers to bring properties to market. If more sellers do come to market and the cost of capital increases as inflation and interest rates continue to stay elevated, the pace of increases in the price per bed for skilled nursing properties may be limited in the near-term.